Most internal comms strategies still treat participation as something that comes later. After the newsletter goes out. After the announcement is posted. After the strategy deck is shared. Feedback becomes an afterthought, invited only when it’s convenient. Employees might respond. They might not. Either way, the system moves on.

But the absence of resistance doesn’t mean the presence of engagement. And when engagement is treated like a postscript, it rarely leaves a trace.

What’s often missing isn’t a better survey tool or a more interactive interface. It’s a system that makes participation feel routine; expected, not exceptional. A structure that invites people to show up before the message is sent and stay engaged long after it lands. Not just to confirm what they heard but to shape what happens next.

This is where the “Engage Me” dimension of the User Needs Model becomes foundational. It reframes engagement as something to be engineered, not measured. Less about clicks, more about continuity. Less about content, more about connection. It’s not a metric you chase at the end of a campaign. It’s the architecture you build at the beginning.

The pages that follow explore what that architecture looks like in practice. Not as a theory. But as a structure. As a set of rituals, rhythms and decisions that invite people to participate not just observe.

How to implement

Embedding engagement into internal communication doesn’t start with format. It starts with friction. Specifically, the amount of effort it takes for someone to respond, contribute or feel that their input matters.

Most comms teams look for ways to make content more interactive. But interactivity without intent is decoration. It doesn’t build trust. And it doesn’t scale. What scales is the infrastructure around participation. The cadence, the clarity of feedback loops, the emotional signal that contribution will be seen, not just collected.

Designing for engagement means creating predictable opportunities to show up, speak up and shape what happens next. It’s not about turning every employee into a contributor. It’s about making it easier for people to participate in ways that suit their roles, their energy and the context they’re in.

It’s also about presence. Not every act of engagement is loud. A short reaction. A comment left in a team channel. A question asked privately. These moments only add up if the system is designed to notice them. And if there’s a plan for what happens next.

The following five implementation strategies are not quick fixes. They’re structural levers. Designed to reduce friction, normalise contribution and create feedback systems that hold.

1. Make feedback predictable

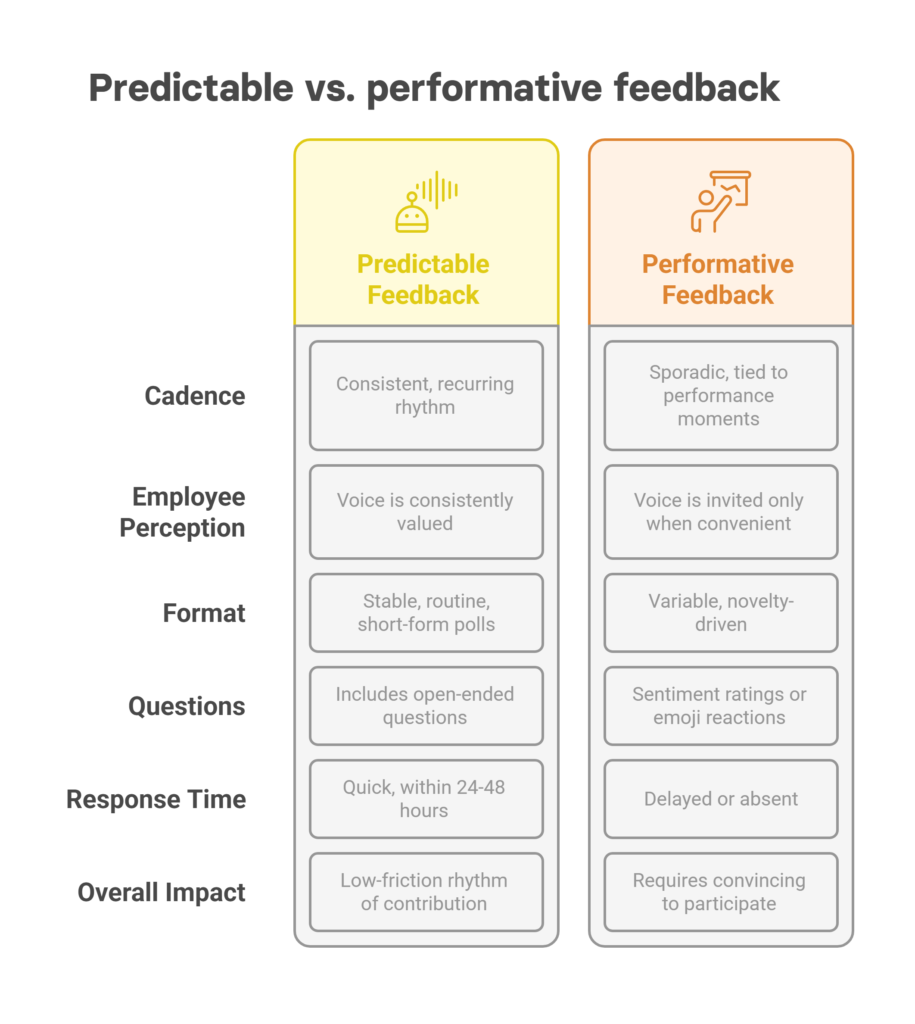

Most internal feedback systems rely on the spotlight. A big campaign rolls out, a leadership update drops and suddenly a survey link appears. The request for feedback arrives not as a normal part of rhythm but as a reaction to visibility. Employees are asked to weigh in after the message has already taken shape. Sometimes after the decisions have already been made.

When participation is tied to performance moments, it becomes situational. People learn to associate feedback with optics. Not listening.

The problem here isn’t the format. It’s the cadence. Sporadic signals create the impression that voice is invited only when convenient. Not when useful. Over time, the habit disappears. Employees assume that what they say won’t travel anywhere meaningful. And they act accordingly.

To rebuild that trust, you have to remove the surprise.

Feedback has to arrive at the same time, in the same places, with a level of consistency that feels almost mundane. Not elevated. Not framed as “your voice matters” every time. Just part of how the system works.

That means:

- Embedding short-form polls in recurring content. Weekly digests, dashboards, app modules. Something that shows up without needing a special send.

- Holding the format stable. Same day. Same structure. Avoid changing questions too frequently. The goal is to build a routine, not chase novelty.

- Making at least one question open-ended. Not just a sentiment rating or emoji reaction. Something that asks, “What are we missing?” Or “What didn’t land?”

- Responding quickly. Within 24 to 48 hours. Summarise what was said. Name what will change. Acknowledge what won’t. The summary is the message. Not the form.

When done well, this creates a low-friction rhythm of contribution. People don’t need to be convinced to participate. They just need to know it won’t disappear into a void.

2. Use real-time formats to shorten the distance between question and response

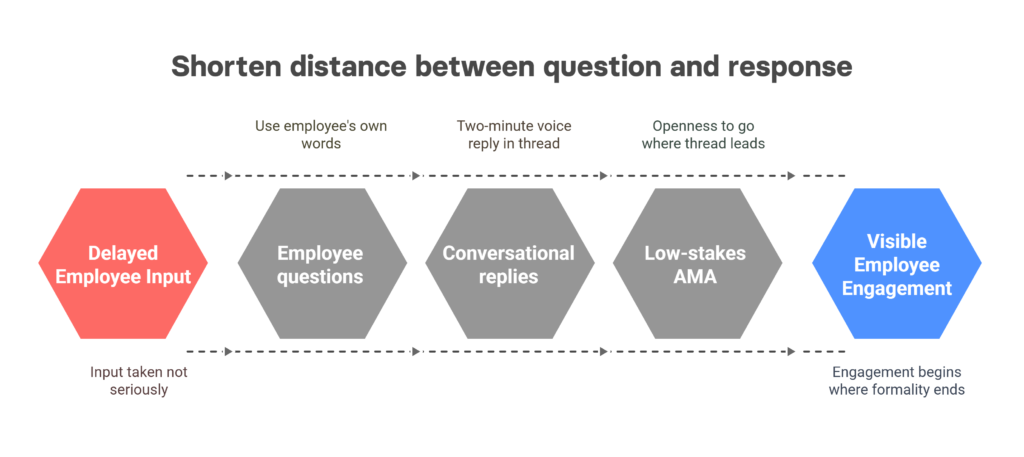

There’s a particular silence that creeps in after most town halls. Not because nothing was said, but because nothing came back. Questions were “collected” in advance. A few made it into the final ten minutes. Answers were cautious. Sincere, maybe, but flattened by timing. Nobody leaves feeling like a conversation took place.

This isn’t about access. It’s about latency. The time between asking and hearing back becomes a proxy for how seriously employee input is taken. And when that delay stretches to hours, days, sometimes weeks, it signals distance. Not dialogue.

The alternative isn’t just faster answers. It’s visible engagement with the question itself. Not a statement. A response. One that reflects consideration, not containment.

That’s why asynchronous formats work well, if they’re used with the right intent. A voice note recorded that evening. A short reply video posted to the channel the next morning. It doesn’t have to be polished. But it does have to sound like the person speaking actually heard the question.

Tactically, that means:

- Letting employees ask questions in their own words. Not reformulated by comms. Not anonymised by default. Voice recordings. Quick videos. Typed notes with context. Give them choice but preserve tone.

- Creating space for reply formats that feel conversational. A two-minute voice reply posted back into the same thread. A Loom-style response with screen and face. A text note that reflects, not reframes, the original question.

- Hosting low-stakes “Ask Me Anything” threads that aren’t performance pieces. No deck. No agenda. Just a window of time, a few seeded prompts, and openness to go wherever the thread leads. Consider giving an option for anonymous participation but don’t make that the only path.

The point here isn’t transparency theatre. It’s contact. An acknowledgement that engagement begins where formality ends. Not when the message is ready but when people are.

3. Open a space for micro-contributions

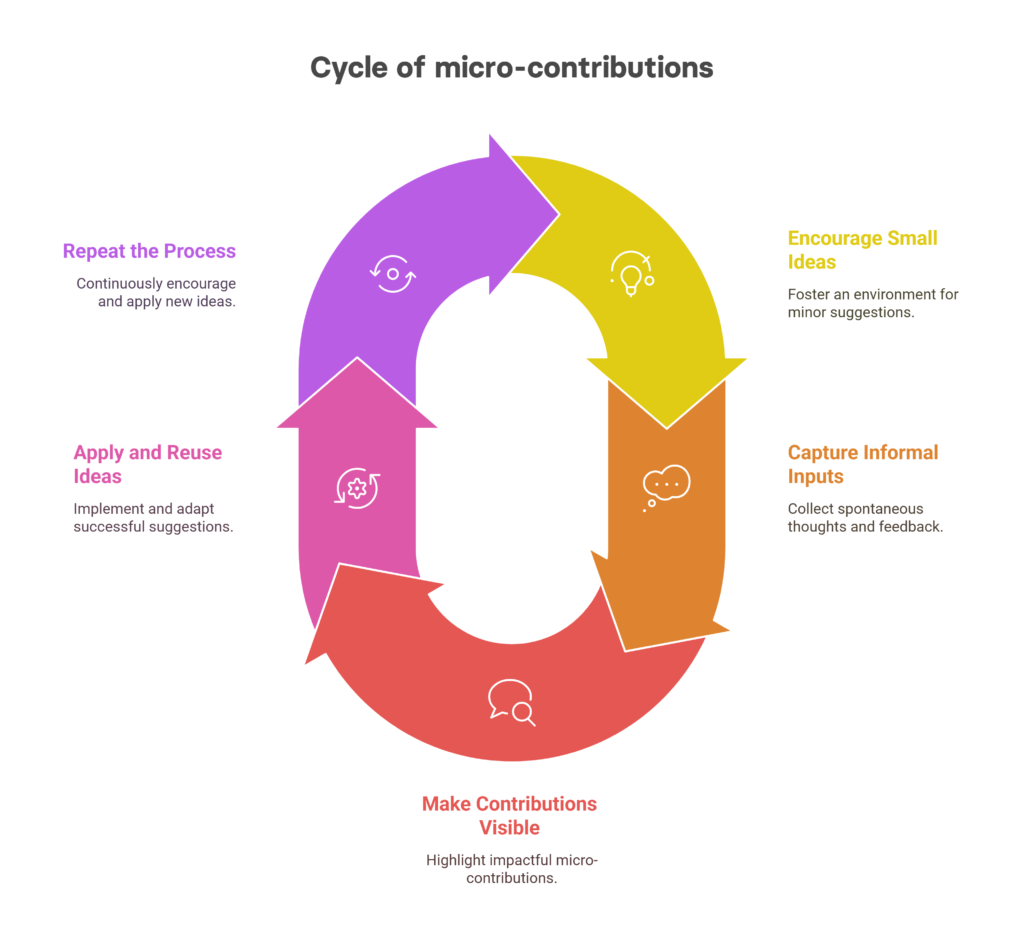

Most organisations reserve their listening for big moments. Brainstorms. Offsites. Innovation sprints. There’s a whiteboard. A post-it wall. A facilitator. People are asked to think bold. Think big. Think future.

But most of what shapes a culture, or improves it, starts smaller. A phrasing suggestion on a policy draft. A one-line reply that reframes a team ritual. A quiet “What if we tried…” in a comment thread that ends up shifting direction.

These aren’t initiatives. They’re micro-contributions. And they usually live outside the official lanes.

The problem is that internal comms systems aren’t built to hold them. Feedback mechanisms are formalised. Channels are structured for finished thoughts. There’s rarely a place to say something half-formed. And even more rarely a moment when that contribution gets seen, shaped and reused.

To shift that, you don’t need more input. You need a better container.

That might mean:

- Creating discussion threads that centre on everyday decisions: “How would you explain our strategy to someone new?” “What’s the best tool nobody knows we use?” “What small process did your team improve this month?” The goal isn’t consensus. It’s texture.

- Enabling response modes that match the tone of these contributions. Polls. Quick replies. Emoji reactions. Fragments of thought that don’t need narrative weight to matter. Lower the effort. Raise the surface area.

- Making visible what usually disappears. Highlight one micro-contribution each week that changed something. A headline that shifted tone, a tweak to onboarding that came from a Slack comment, a naming idea that landed. Not as a showcase. Just as signal.

This isn’t about flattening all feedback into content. It’s about elevating the informal cues, the things people say in passing without agenda, so they can shape the system without needing to petition it.

4. Design engagement rituals

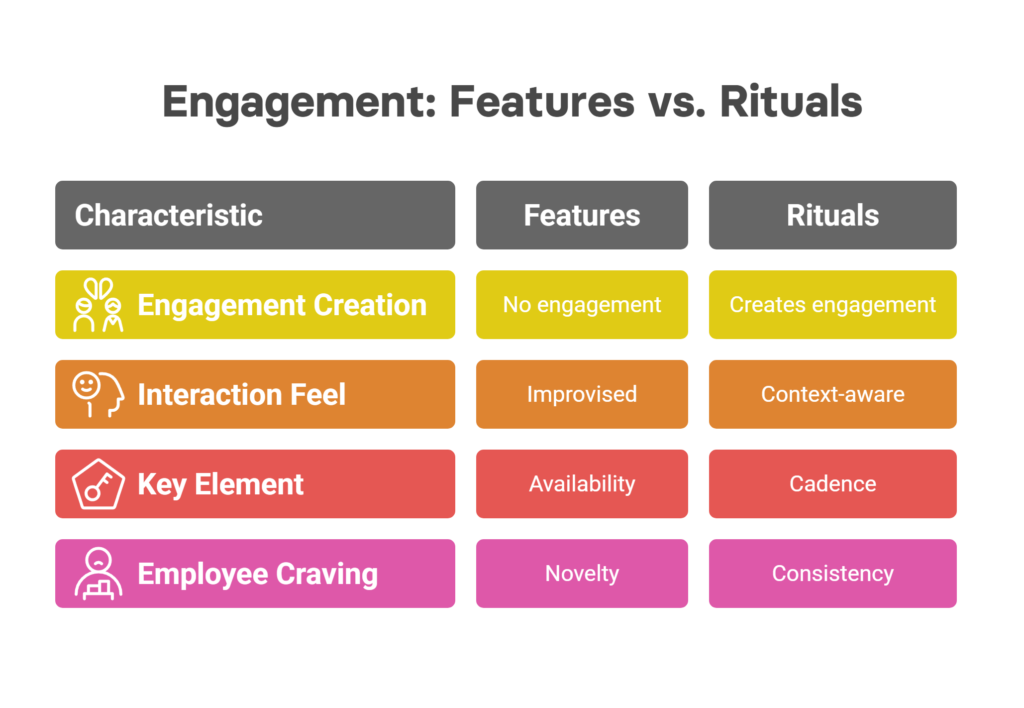

It’s easy to confuse feature availability with behavioural design. You roll out a comment thread. A reaction button. A survey tool. The functions exist. But they don’t get used the way you hoped, or worse, they get used once and disappear.

Features don’t create engagement. Patterns do.

People don’t participate because a channel is open. They participate when the rhythm is familiar enough to lower resistance. When they know what’s expected. When they’ve seen what came of it before. When the interaction doesn’t feel like a test.

Without cadence, interaction feels improvised. And improvisation doesn’t scale.

What works instead is ritual. Not in the ceremonial sense but in the design sense, a repeated, context-aware moment that makes participation easier, safer and more likely over time.

To get there:

- Start with low-friction repeatables. A weekly digest called “What We Heard” that pulls highlights from threads, polls and side-channel conversations. No fancy visuals. Just a signal that someone was paying attention and curated the signals.

- Create named formats. Something employees can refer to by shorthand. Maybe it’s “Ask Us Anything Week” every second month. Maybe it’s “Team Pulse Fridays” where each unit posts one insight from the week. The point isn’t what you call it. It’s that it becomes legible over time.

- Blend ritual with reward but not in the transactional sense. Avoid leaderboard logic. Instead, highlight a pattern: “Three projects this quarter were shaped by employee-suggested tools.” Signal influence, not score.

- Make it cumulative. Quarterly “culture capsules” that wrap up learnings, peer ideas that made it into playbooks and reflections from those involved. The capsule becomes a form of collective memory. Not a report, but a record.

The mistake most internal comms teams make is thinking that engagement needs to be constantly novel. But what people crave isn’t surprise. It’s consistency with room to contribute. A structure that stays, even when the topics change.

5. Build loops, not walls

Most organisations say they welcome feedback. Fewer can point to where that feedback went. Fewer still can name what changed because of it. And this is where trust begins to decay not because people were ignored, but because they were invited in with no way to see where they landed.

One-way feedback collection looks like progress. It looks like a survey. It looks like a suggestion box. But structurally, it behaves like a wall.

People speak. The system listens or says it does. Then everything goes quiet.

The loop breaks when action isn’t visible, when responses are delayed or when the mechanism for acknowledging contribution is missing altogether. It’s not the silence that does the damage. It’s the ambiguity. The feeling of speaking into a system with no edges, no return path, no signal that the input changed anything at all.

Closing that loop isn’t about promising implementation. It’s about showing that the response itself is part of the structure. That people’s time, ideas and reflections live somewhere real.

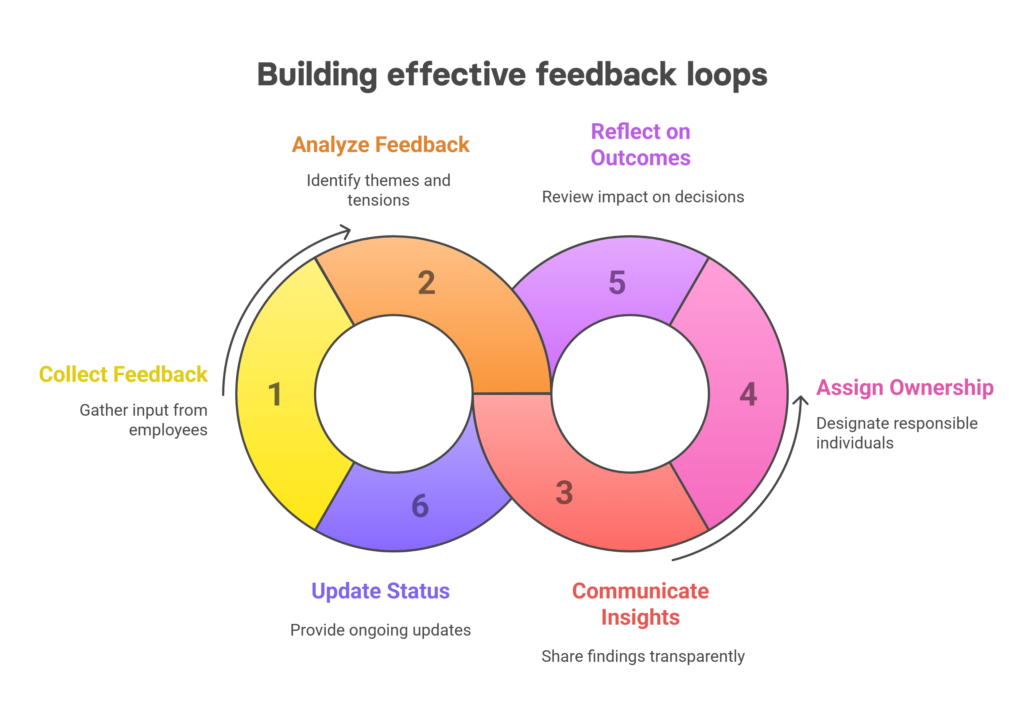

To build that loop into internal comms:

- Pair every major feedback moment (survey, discussion, comment thread) with a transparent “What We Heard” post. Not just a digest, but a map of themes, edge cases, tensions. Include the messy parts.

- Introduce a “status board” for open ideas or ongoing concerns. Keep it accessible. Keep it updated. Even a tag like “Still exploring” shows more honesty than silence.

- Assign visible ownership. Someone whose name appears next to an open issue or theme. Not as a promise of resolution, but as a sign that accountability isn’t abstract.

- Build in reflection moments. A quarterly email or short video summarising what input shaped what outcomes. The message isn’t “we did everything you said.” It’s “we paid attention, here’s how it shaped our choices.”

- Use language that reflects movement. “Still gathering insight.” “Trying a test run.” “Shelved, but archived for future use.” Let employees trace the idea’s arc, even if it doesn’t lead to implementation.

How to know its working

Engagement doesn’t usually announce itself. It doesn’t spike like traffic or sit neatly on a graph. Most of the time, it arrives in fragments, side comments in a meeting, a quote pulled into a team update, a quiet nod to something someone said weeks ago.

That’s the paradox of participation. When it’s real, it feels ordinary.

Which makes tracking it less about dashboards and more about signals, some visible, some ambient. The challenge is knowing what to pay attention to and where.

You’re not measuring noise. You’re looking for indicators that people feel the system is open enough to speak into and structured enough to expect a response.

What to look for:

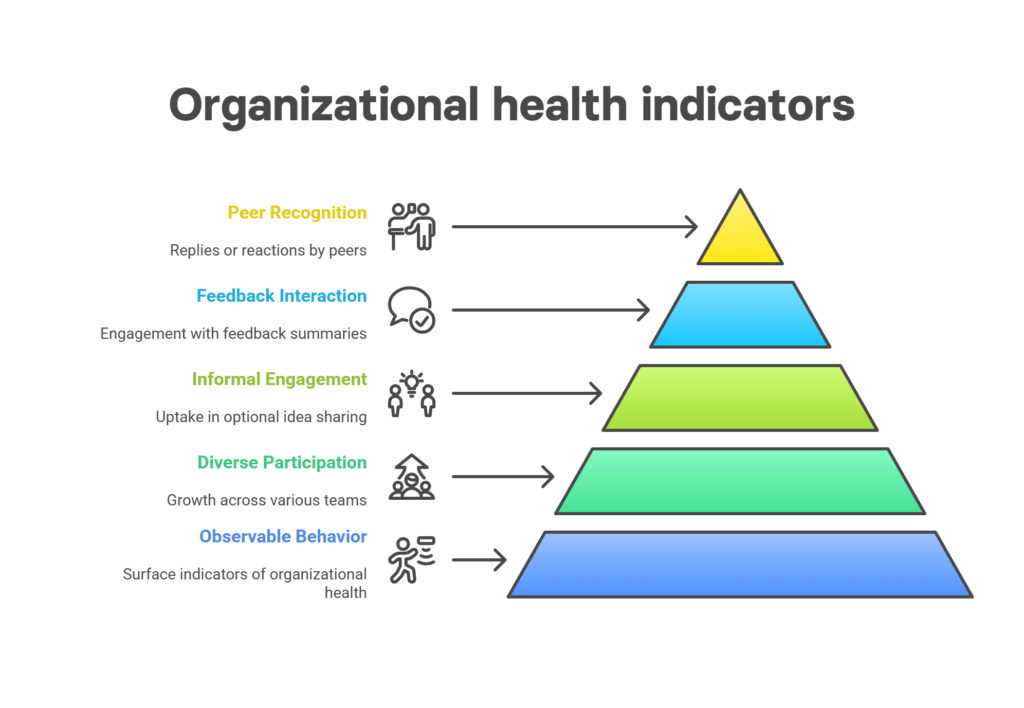

Observable behaviour

These are your surface indicators. Quantitative. Trackable. Often undervalued because they look small in isolation, but collectively, they signal health.

- Steady growth in poll or comment participation across diverse teams (not just the same high-responding groups)

- Uptake in optional threads or informal idea sharing, especially outside structured prompts

- Engagement with feedback summaries or follow-up posts (not just original input moments)

- Replies or reactions on contributions by peers (not just leader-led moments)

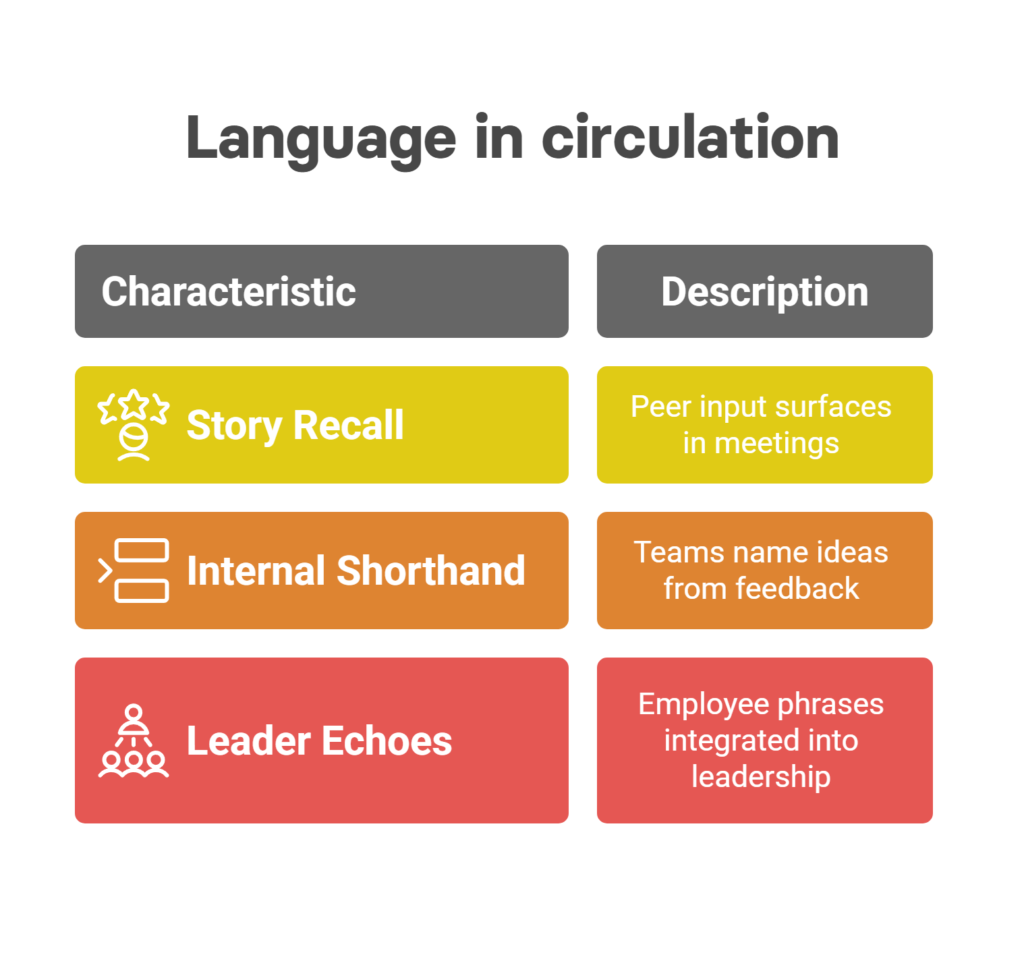

Language in circulation

If feedback loops are working, you’ll hear it, not in slogans, but in how people speak about work. Language is a proxy for internal culture. If employees start referencing what others said or if leaders casually cite a comment thread or AMA question, something’s sticking.

- Story recall: a moment of peer input showing up in meetings or retrospectives

- Internal shorthand: teams start naming ideas that originated from feedback (“That’s the thing Raj mentioned last month”)

- Leader echoes: phrases, questions, or critiques from employees folded into leadership communication without attribution, because they’ve become part of the thinking

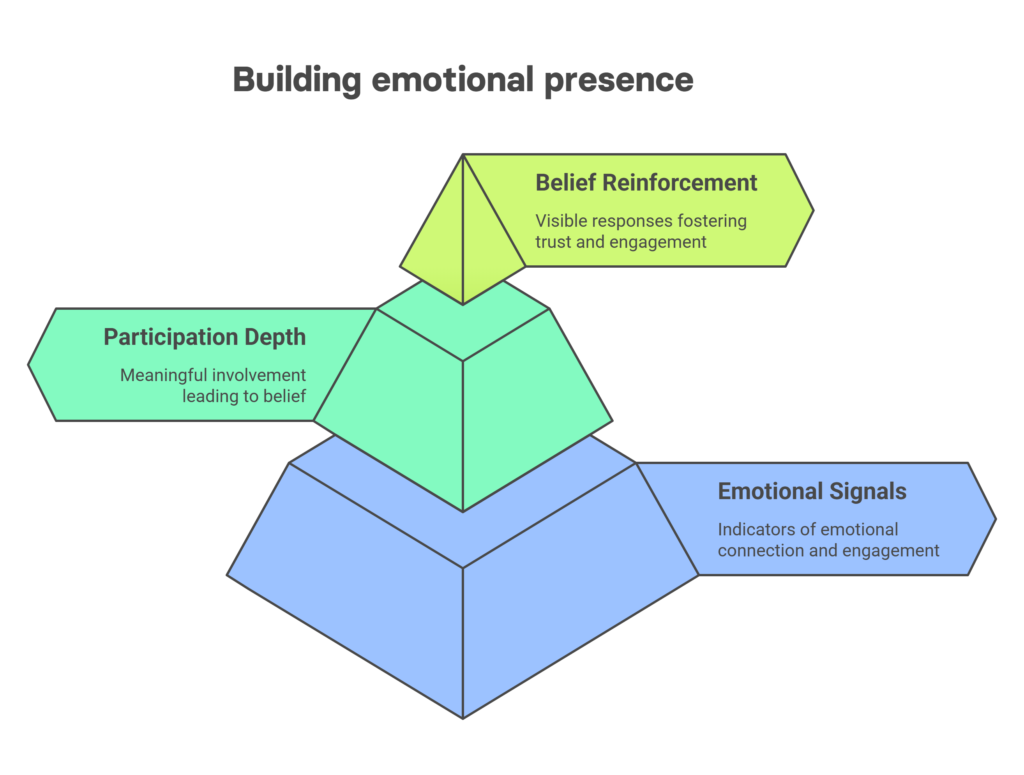

Emotional presence

These signals are harder to surface directly. But they show up in trend lines, retention indicators and spontaneous contribution.

- Pulse scores on feeling seen, heard or included trending upward

- Decrease in attrition reasons tied to “lack of voice,” “not being valued” or “disconnected culture”

- Rise in proactive contributions, feedback shared without prompting, employees creating new rituals or engagement formats themselves

What matters here isn’t volume. It’s depth. Participation that results in nothing teaches silence. But participation that results in response, visible, thoughtful, even imperfect, teaches belief.

That’s the signal you’re looking for.

Why “Engage me” works (the evidence)

👉 According to Achievers’ 2024 State of Employee Recognition report, 69% of employees are more likely to remain with a company that regularly recognises their contributions.

👉 The State of Workplace Empathy study found that 96% of employees believe empathy is essential to retention, illustrating how two-way communication helps employees feel heard and valued, which is vital for retaining talent.

👉 According to Gallup, 80% of employees who received meaningful feedback within the past week reported being fully engaged at work, regardless of their in-office attendance.

The true test of two-way communication

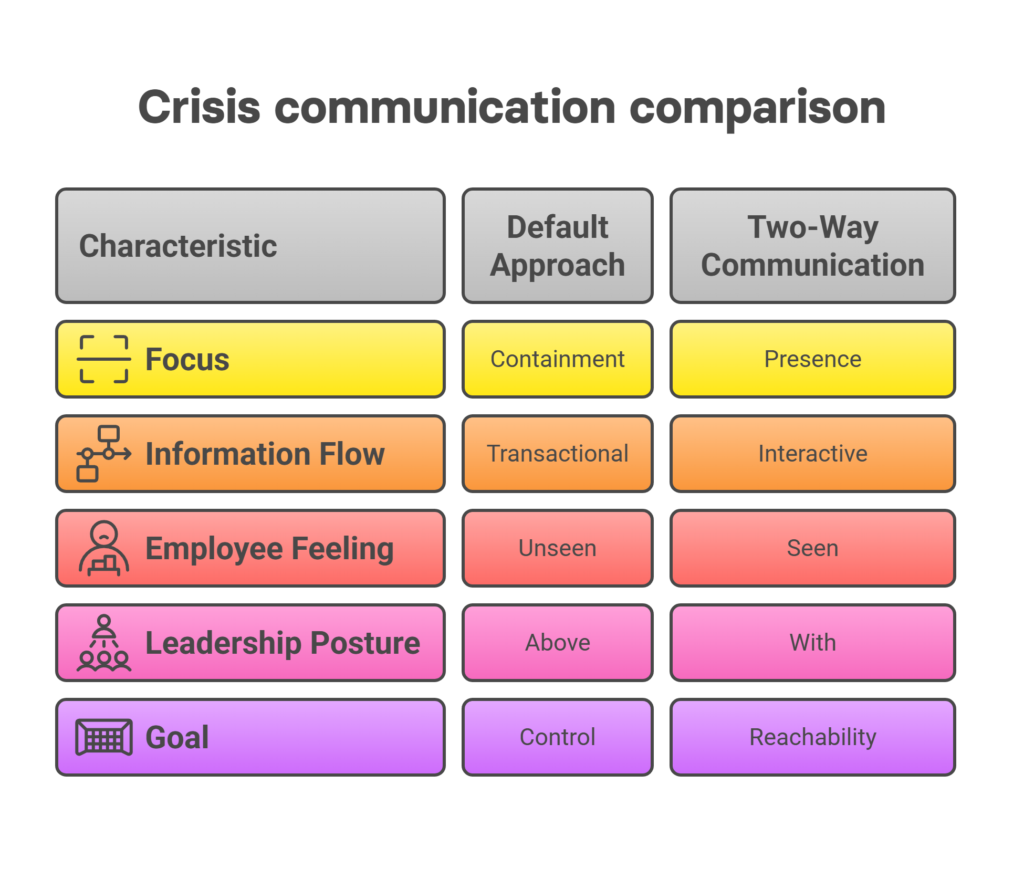

It’s easy to talk about engagement when things are stable. When the waters are calm and the stakes are low, most systems work. Polls get answered. Comments trickle in. Recognition feels timely. But during a crisis, when trust is brittle and attention is strained, that’s where the real test begins. And that’s where most organisations revert to default.

The instinct is usually to contain. To communicate tightly. To focus on control, speed and clarity. The problem is, people aren’t just looking for updates. They’re trying to locate themselves in what’s happening. And when internal communication becomes strictly transactional, participation dries up. Not because people stop caring but because they no longer feel seen.

The difference isn’t in the information. It’s in the posture.

During the pandemic, Airbnb made the decision to hold direct town halls where any employee could ask leadership a question. No filtering, no scripting, no stagecraft. The company didn’t try to polish the unknown. They let it be visible. And in that visibility, something else emerged: contact.

When things are falling apart, people don’t need spin. They need presence. Someone who will sit in the uncertainty with them not above them. That’s what two-way communication makes possible, even when the answers aren’t ready.

Implementation guidance:

- Open the floor early. Don’t wait for a fully formed narrative. Use pinned threads, live polls or even anonymous prompts to ask: “What are you most unsure about right now?”

- Follow up with frequency, not finality. Sometimes the most valuable message is: “We don’t know yet but here’s what we’re doing next.”

- Recognise the signals that aren’t raised hands. Who’s quiet? What topics keep surfacing in comments? What isn’t being said, but sits between the lines?

- Assign responsibility for follow-through. It doesn’t always have to come from leadership. What matters is that someone responds. That the loop closes, even if the answer is imperfect.

What Adobe did differently

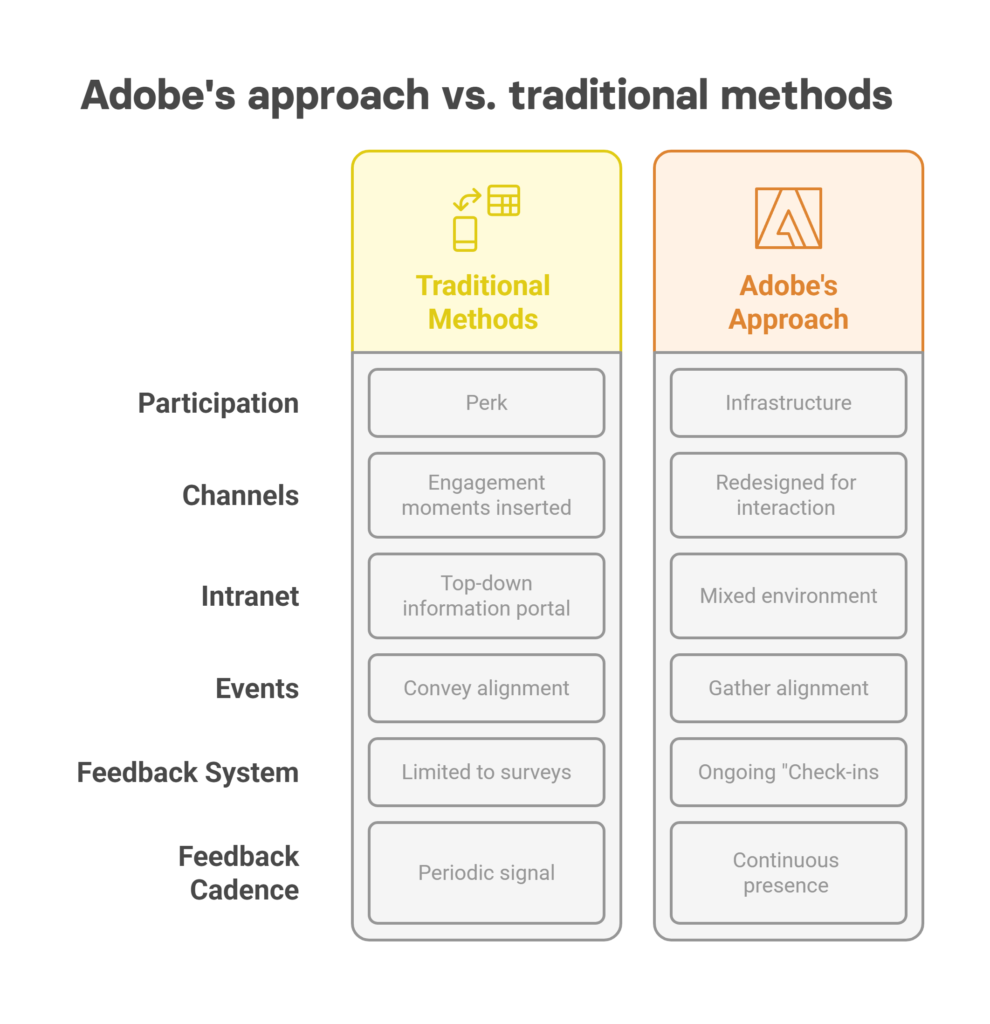

Adobe didn’t approach participation as a perk. They treated it as infrastructure.

It wasn’t about inserting engagement moments into existing channels. It was about redesigning the channels themselves, so interaction wasn’t a separate task but the default state.

This shift showed up in more than just policy. It showed up in how they wired the employee experience. Their intranet, “Inside Adobe,” wasn’t positioned as a top-down portal of information. It became a mixed environment: part newsfeed, part recognition space, part feedback loop. Content wasn’t just broadcast, it was shaped by the people reading it. Recommendations surfaced based on role and location, yes, but also based on behaviour. Relevance wasn’t assumed. It was earned.

Their events weren’t structured to convey alignment. They were built to gather it. “Adobe for All Week,” for instance, didn’t just feature speakers. It featured employee-led sessions, opt-in discussions and real-time feedback. Leadership didn’t just appear, they stayed. They listened. They responded, not with closing statements, but with continuation prompts.

Their feedback system wasn’t limited to surveys. It included ongoing “Check-ins,” an initiative rooted in manager-employee dialogue. Regular, informal. Not tied to performance reviews. No quarterly build-up. Just space for reflection, forward-looking clarity and small course corrections, before misalignment calcified.

This is what Adobe got right: they didn’t assume feedback was a periodic signal. They treated it as a continuous presence. One that needed tools, not just templates. Systems, not sentiments.

It’s tempting to see Adobe’s model as a product of its scale. But the principles aren’t proprietary. The mechanics of contribution scale in both directions, only when made visible, habitual and respected.

And when those mechanics are baked into the way people experience work, participation stops needing encouragement. It becomes a feature of the culture itself.

Why engagement must be built, not requested

You can’t rely on individual enthusiasm to carry the weight of participation. Enthusiasm fluctuates. Systems hold.

When employees engage once, it’s a signal. When they return, respond, refer and contribute without being nudged, it’s structure doing its job.

What makes that possible isn’t more content or louder campaigns. It’s quiet consistency. Rituals that ask, but also answer. Formats that adapt to the grain of how people already work. Feedback that doesn’t just get collected, it gets traced. Back to decisions, policies, product direction, team dynamics.

None of this is dramatic. And none of it is fast. It requires giving up the performance of engagement (the spikes, the stats, the slogans) in favour of something harder to build and easier to trust.

A system that doesn’t just send messages out, but receives them in. Holds them. Works with them.

This is what the “Engage Me” dimension makes visible. That participation is not a follow-up to communication. It is part of its design.